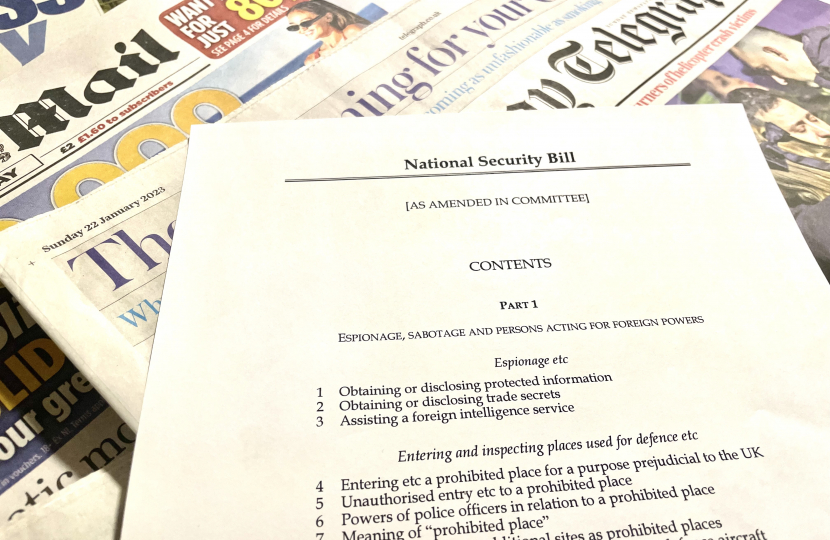

The National Security Bill, currently before Parliament, poses a grave threat to whistle-blowing and investigative journalism says a coalition of more than 40 international media freedom organisations.

Guy signed the letter as Chairman of the Commonwealth Press Union. (The text of the letter, published in The Times on 11th January, and list of signatories is here.

He intervened in the debate on the Bill in the House of Lords later that day to explain why the Bill potentially criminalises investigative reporting by making it a criminal offence - with severe sanctions - if a journalist "ought reasonably to know" that reporting is a threat to national security. It would, he said, not just stop major investigations like the Panama papers, but hinder reporting on any public interest stories where national security might be involved - such as Telegraph reports on Chinese influence in the UK. There is no public interest defence in the legislation for journalists or whistle-blowers.

Guy told the Lords, which can also be watched here:

My Lords, I speak in support of Amendment 66A in the name of the noble Baroness, Lady Jones of Moulsecoomb. This really important amendment gives us a chance to look at the Bill’s potential impact on investigative reporting.

I support this Bill, which rightly tackles the grave threats to the security of our country; I am sorry that I, too, was unable to speak to that effect at Second Reading. I support this probing amendment because it highlights a substantive issue arising from the Bill that relates to public interest and investigative journalism. Although more could be done—I will mention a couple of points in a moment—this is a limited, practical, technical amendment that does not in any way impact on the Bill’s vital central mission but deals with a serious threat to media freedom.

I do not for a minute believe that this Bill’s provisions will be used regularly to prosecute journalists but, crucially, I do believe that there are circumstances where it could be deployed to stop a major piece of investigative reporting—I will explain why—because of the subsequent chilling impact on investigative journalism, not least because of the rightly high, heavy sentences involved. I also think that there are major issues of press freedom globally on this point because the way in which we legislate in the UK, especially on issues of national security, tends to be copied in a much more dramatic fashion in far less democratic countries; this issue was powerfully raised in a letter from international press freedom organisations that was published today in the Times and which I co-signed as chairman of the Commonwealth Press Union.

I want to make one general comment before I come on to the specifics of this amendment. For more than 25 years, I have been involved in one way or another in major pieces of legislation that are not intended to have any impact on the media. However, unforeseen consequences often become apparent as they are scrutinised and the potential risk becomes clear. On almost every occasion, Governments of every persuasion have acted to amend a Bill to protect the legitimate interests of media freedom. I believe that this is one such occasion when the Government or this House should act when problems become evident. Where public interest journalism is concerned, we must always act with the utmost caution.

Let me explain the crux of the problem. Modern public interest journalism in a digitally connected world inevitably straddles national boundaries. It involves a combination of civil society and media organisations working together to report on leaked documents from the public and private sectors, the publication of which is genuinely in the public interest. It often relies on whistleblowers, who expose themselves to serious risk, and those who provide information that substantiates the truth of claims. The Panama papers and the Uber files are two such investigations, but this point also applies to straightforward reporting, such as that by the Daily Telegraph on Chinese influence in the UK and British citizens being placed on a Chinese watch-list; the reporting of the Daily Mail on the horrific experiences of female submariners on-board nuclear submarines; and the BBC’s story last year about a spy who used his status to terrorise his partner before moving abroad to continue intelligence work while under investigation. You can see how arguments might be made about any of these reports potentially being of use to a foreign intelligence service.

The problem arises because of the wide definitions used in Clauses 1 and 3 and particularly at the foreign power condition in Clause 29. Together, they could potentially criminalise one of the core functions of journalism: reporting on leaks of information about Governments, organisations and companies. They could cause problems for civil society organisations that work legitimately with journalists on investigations if those organisations are funded by foreign Governments, many of whom, like the United States, are of course sympathetic to the UK. They could cause serious problems for sources, who might reveal restricted information such as trade secrets when disclosing information clearly in the public interest to organisations that accept financial assistance from foreign states. They could cause serious problems for those collaborating with UK and international organisations which receive funding from foreign Governments. The admirable Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, to take one such case, receives donations from the US Department of State and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. As we have heard, there is no distinction in the Bill between hostile and friendly sources of funding which would provide protection for such collaboration.

These might all be theoretical issues, as I am sure that my noble friend will say. When it comes to media freedom, history shows us that we must take the utmost care with problems of theory. However, one issue is most certainly not theoretical: the chilling impact that results from the combination of all these pitfalls and from this clause. When the potential sanctions under the Bill are so grave, would whistleblowers really want to take the risk? Would those involved in an investigation who might be needed to corroborate information be willing to take the chance? Would journalists want to put themselves and their editors and publishers in jeopardy? Would civil society organisations affected be prepared to do so? I suspect that the answer to all those questions is no, which would have significant repercussions for investigative reporting, particularly on international matters, something that the Bill never intended to do. The key point is this: journalists and whistleblowers may fall within the scope simply because they ought to have known a story about how a Government might assist another country. That is an incredibly low bar and cannot possibly be right.

The Bill does not need major surgery to deal with these issues. Instead, it needs the tightening up of the foreign power condition and the wording in Clauses 1 and 3. Ideally, as well as looking at this amendment, the Government will think again about Amendments 65 and 66 tabled by the noble Lord, Lord Marks, which have already been debated. Sadly, I was unable to contribute to that debate. Further technical amendments and tweaks to language will be needed in relation to the search powers in Schedule 2. Amendment 75 tabled by the noble Lord, Lord Marks, which I support, would also be helpful.

There must be a holistic approach to the problems of journalism arising from this Bill. I would be grateful if my noble friend could look again at that issue in the light of this debate and consider two points, both of which arise from the amendment moved by the noble Baroness, Lady Jones.

First, “ought reasonably to know” in this clause is a low bar when the Bill is aimed at those who absolutely know what they are doing because they are involved in espionage. Let us raise the bar and not potentially criminalise whistleblowers—who already put themselves in serious danger—civil society organisations and journalists by taking that criterion out.

Similarly, we should ensure that the Bill’s provisions are aimed at those deliberately carrying out something which they know prejudices or is intended to prejudice the safety, security or defence of our country, not those who stumble into the purview of criminal sanctions while doing their job in the public interest. I am very grateful to the noble Baroness, Lady Jones, for tabling Amendment 66A, as it deals with a serious problem in a technical and proportionate way that in no way undermines the vital purpose of the Bill.

I very much hope that my noble friend is able to respond positively to this debate, either by bringing back an appropriate government amendment protecting media freedom on Report or, at the very least, giving a powerful signal from the Dispatch Box that the Bill is not aimed at journalism and those who work with journalists, or at hampering investigative reporting.

The full text of the debate - including the Government's response - is here (staring with Clause 29).

ENDS